Getting Started on Financial Independence: Financial Resiliency

My COVID Career Advice post had a key section on making yourself financially independent. It was more popular than I would have guessed and spawned backchannel chats with people on how best to get started on financially resiliency. This post is a round up of the advice I’ve given people who asked. YMMV. Nothing in here is rocket science, though it requires a commitment, some setup, and some habits (or discipline) around taking your financial health seriously. Behaviour change is key.

This post deals with basic hygiene and financial resiliency: putting yourself into a position to start moving towards financial independence. A future post will deal with getting started investing and how to plan and timeline out financial independence.

Longer Range Goals

Let’s talk first about what your larger goals are here: Financial Independence (FI) is about giving you choices .

The less dependent you are on an employer’s stream of income keeping you financially viable, the greater control you have over your life. If you’ve fallen into the trap many have and expanded your expenses as your income has increased, or taken on debt in order to move future earnings into present consumption (which comes with costs), you may not have as much freedom as you’d like regardless of looking wealthy from the outside.

This is independent of how high your income levels are. Even people earning high incomes get trapped in jobs simply because their finances are not under control from poor financial choices. Over-extended mortgages or rent, expensive cars, credit card debt, questionable crypto investments, and similar have people hemmed in worse than people earning much less, but making smarter financial choices. While higher earners may have greater access to credit (and banks more willing to loan to them) that may even make their situation worse.

So, what precisely do we mean by financial independence? What is the longer term goal? How do we know we’ve achieved it? If you’re financially independent you have:

- Expenses under control

- Minimal-to-no short term consumer debt

- An emergency fund against contingencies

- Income streams from assets covering your expenses completely

Once income streams from assets cover your expenses, you’re largely independent of needing a job. Even before you get there, having alternative income streams from equities, businesses, rental income, or similar puts you in a position to make other choices about your life not defined by your job. Scaling back from corporate grinder roles, moving to part-time roles to focus on other priorities, or even taking a more personally fulfilling, but much lower paying job than what you currently are doing are all options. You have choices.

Ticking off item number 4 is financial independence and the ultimate goal. We’ll discuss how to get there in greater detail in a future post.

This post is about the first three items which are pre-conditions to get to number 4. Think of this post as being about financial resiliency.

Getting Started - Simple Rules

I know it sounds too simple, but much like advice about eating properly, getting enough sleep, and exercising regularly, few people give their financial health enough thought until there is a crisis.

Getting yourself into better financial shape is not rocket science. It may require unlearning bad habits and possibly making some major changes in your lifestyle, but ultimately it’s about good behaviours. It’s about following simple rules and developing some key habits. The guidelines here can help you achieve more financial resiliency (and path towards independence) even if you have zero savings and considerable credit card debt. Don’t get discouraged if you are in this camp.

One other piece of advice: Try and make these changes part of your identity. You need to want to be the type of person that is sound financially and makes good financial decisions, rather than trying to look like you’re living large and a celebrity instagrammer. It may sound silly, but altering your sense of financial identity makes a big difference in terms of how you start to see your decisions and choices (and even your risk profile). Try to put your ego in check. I find there is a close correlation between people trying to use expenditure as cheap economic signalling and those in financial trouble (the fake it till you make it crowd). Habit formation tied to identity change is usually vastly more successful than not re-picturing yourself as someone better.

So, let’s get started with a few simple rules:

The Rules

- Live on 80

- Pay yourself first

- Have a 6 month emergency fund

- Use credit wisely

1. Live on 80

Live on within your means. Track your spending. Spend Less Than You Make.

Despite the fact that spending less than you earn would seem to be an obvious to most people, easy access to credit blurs the line too easily in our consumeristic culture.

My advice is live on 80. Live on 80% of your take home. Use the other 20% as your contribution to financial independence.

Yes, for some people 80% is a hard bar to meet. And may require sacrifice and discipline. For many others, it’s simply being less sloppy and making more sustainable financial choices. There’re some easy ways to figure out how hard this is going to be for you though.

Let’s get started with an exercise to take stock of your spending.

The goal here every month is to look at what you spent categorically, tweak, reset, and figure out how to course correct. I hesitate to call it budgeting since you’re actually trying to make sure your topline does not exceed 80% (and do note, if you can’t live on 80% due to things being tight, 85% or 90% works too. FI just takes longer.). You do need to track a bit monthly to make sure changes in behaviour are taking and that external factors (eating out more, your ride hailing company becoming a monopoly) are not changing and slowly tipping you above 80, but overall, it’s lightweight and pragmatic and should take very little time each month. Though discipline may be an issue.

I put my monthly financial review in my calendar (and GTD app) every month so I don’t “forget” to do it (#protip at first this feels hard and onerous as you get the flywheel started). Once you get into the groove and have a couple of months under your belt, doing your monthly finances feels pretty good since you feel like you’re moving forward and winning at life.

A Little Financial EDA

To get started, we need to do a bit of Exploratory Data Analysis (EDA) on your finances.

We’re going to look at where your money comes from and where it goes. You’re going to need to collect payslips, your last couple of bank account statements, or wing it if you have a good grasp of the numbers (and I bet you may think you do but you don’t). The goal here is to figure out your budget actuals from what they need to be to live on 80 and figure out what changes to make.

You are gonna need a spreadsheet like Google Sheets, Numbers, or Excel, or a cooler tool like Calca . You can also use more sophisticated commercial financial tools and some online banking systems that have this functionality (Mint etc). The tool is not important, the understanding is . So, use whatever is simple and you are comfy with and can save and refer back to later. This is a living document. You need to see your original plan and track to it. Since most people get paid monthly, we’re going to work on a month scale and figure out what categories of stuff your money gets spent on.

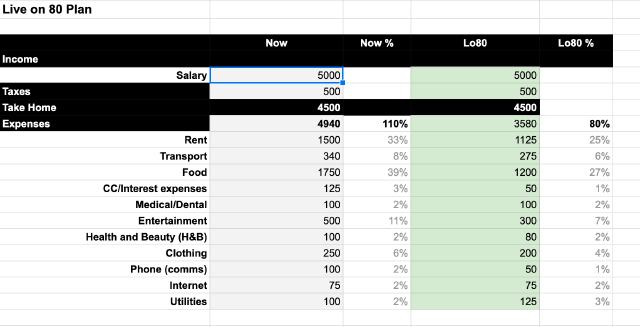

Put something like this together:

You can make a copy of the Google Sheets example (numbers for illustration) for yourself to save time.

We’re going to fill in the Now column, to give you an idea of what you’re spending and where.

Income should be easy for most people since it’s what you get paid monthly and should be on your payslip. If your taxes are already pulled off your paycheque automatically, great. If you are like me and live in a country where they pay you the gross and you’re responsible for paying your taxes each year, let’s subtract an estimate of your tax liability off the top right away so you don’t find yourself in trouble come income tax time.

Now comes the hard part: categorizing expenditures. I advise categorizing in larger groups by what service or job things provide to you rather than thing itself (eg. transport instead of car). Why? It makes it easier to determine what value a thing is providing in your life versus its cost and look at substitutes or replacements.

Adding things up is more a matter of being roughly correct rather than precisely. Your biggies as per the list below:

- Taxes

- Housing

- Transport

- Food (I split this into Groceries, Delivery, and Restaurants)

- CC/Interest expenses

- Medical/Dental

- Entertainment

- Health and Beauty (H&B)

- Clothing

- Phone (comms)

- Internet

- Utilities

Get numbers in there and figure out what percent of your monthly take that is in the column to the right. Your biggest expenses you can do things about (though I do suggest speaking to an accountant or bookkeeper about whether you can reduce your tax liability since it can dramatically change your situation and most people do not take advantage of deductions like they should). Your big items are going to be Rent/Mortgage, Transport, and Food but it’s a good idea to take a look at all your expenses (esp if they’ve modified over the last year from what they may have been due to covid). These big categories are also the things that align most to peoples’ big ticket expenditures: house, car, and sustenance.

Don’t get disheartened if you find you’re actually at well over 100% of your take home when you add everything up. It’s more common than you think (and invisible to some people using credit cards) and our next step will be looking at each of these areas and trying to understand how we might get to our goal of living on 80.

The green column is where you can play with your numbers figuring out what sort of whatif scenarios can get you down to 80%. It’s up to you to figure out what you are willing to alter (some numbers may have to increase, after all - not going out as much generally correlates with a higher utility bill) to get to 80.

What makes good percentages in each category? My observation is that it differs by category internationally but ultimately it does not matter as long as you are comfortably within 80% each month. A couple of guidelines though:

- Housing: if you are at 25% of the 80, you are in good shape. At above 25% of your gross (not take home, not 80) most banks will consider you a credit risk, at least in North America. For the super ambitious amongst you, try to get this down to 10%-15% of your 80 and you are in spectacular shape. If you are also paying this into equity instead of rent on an appreciating property, you’re doing even better.

- Transport: is controversial, but quite frankly most people overspend especially if they are a car owner. Controversially, I would say this should never exceed 10% of your 80, though between this and housing, if you can mange the two of these so they are never above 35% (1/3) you can trade off things like distance to work and expense of accommodation to transportation costs (for example, I hate commuting and the time it takes, so live close to work which raises rent, but reduces transport costs dramatically - generally since I can take advantage of ride hailing or public transport or walking).

- Food: This depends highly on your personal tastes and time available for food preparation as well as if you consider dining out a form of entertainment. I feel 15-20% of the 80 makes sense here.

You’ll notice that this means that ~50% of your 80 budget is taken up by essentials before you even get to things like phone, internet, entertainment, medical, etc. A bit frightening, but remember this leaves you with the other half of your income (or somewhat less if you could not hit those bars) to manage everything else, and still have a solid 20% to invest in your future.

There are things you might be a bit more disciplined about that are simply automatic habits you just keep doing. My particular bad points were to continue to keep paying rent on a place I knew was overpriced (simply due to the search cost of a new place and hassle of moving,) eating out way too much (ordering in actually started saving cash as well as giving me the time to cook), and cleaning up a bunch of things I continued to pay for but did not use. As a general trend, I imagine most people reading this post do some things because they are time poor and pay to make that go away. This is your chance. It only requires a little math and creativity.

I’ll talk in another post about all the things I did since they are almost embarassingly minor in some cases but had huge effects, but overall look at what can be changed in what you have. Moving to a smaller or cheaper place is one of your best options. I literally moved 600m down the road and halved my rent into a flat as big as my old one, with a better kitchen and bathroom, home office, and am now kicking myself I did not move earlier. Rather than have a car, doing the math meant ride hailing was one-fifth the cost (despite the fact most people socially seem to own a car here in Singapore to flag being successful).

My point here is, even though you may not think you have options, you probably do. Most of mine were re-architectings default habits in ways which had large financial consequences after an initial hassle of one-time changes and rebuilding those habits.

Alright now we’ve managed to get to this point, you have a rough idea of what you should be spending each month. Or at least what a max is in each area. Now figure out how to actually get there. What changes can you make.

Tracking

The other thing in here you need to do is to check that once you make the changes you are actually sticking to plan. Yes, tracking.

Everyone hates this. If you are with a good bank or have one of the nice money services connected to your bank, this is automatable. My life is a bit complex due to international entanglements, so I have a crazy system that works in plain text, with multiple currencies, my portfolio, and (no I am not kidding) a bit of machine learning to automate extracting the categories out of monthly csv bank statements. Also, tracking is optional, if healthy, if you have a large enough buffer below 80, you can just make sure you are within that range eveny month and ignore tracking entirely. I found I needed to track because my goals were more aggressive, but the fact of the matter is setting aside 20% and always making sure you pay ourself that amount absolves a lot of financial sins.

2. Pay Yourself First

Not a new or original idea, but consistency and making sure you have money to actually invest is your best friend when trying to get to financial independence. If you can automate forcing yourself to live on 80, you’ll be a lot less inclined to do crazy things with the “extra” you see in your accounts.

As soon as you know you can live on 80, set up a system that automatically moves 20% of incoming income first before you do anything else with your money. Why? Unless you are very organized (or have an amazing Todo system), this will fall off your plate at some point, or you will be tempted to cheat on it in some way when you have some sort of crunch. It’s too easy when things get tight (and they always do) to simply skip a transfer rather than finding better ways of handling the situation. If your bank or such does not offer auto transfers, set this up as a recurring, scheduled calendar appointment with yourself to make the transfer before anything else happens.

Automate the transfer to sweep your account when you get paid and send it on to your investments (or emergency or other similar account). If you also have some way with your brokerage to automatically invest that for you (say in ETFs or such), even better since it’s completely automatic and you are also taking advantage of dollar cost averaging on top of regular investment.

While this sounds like a silly hack, I’d have to say that for many people, this enforced, default consistency goes a long way towards helping them achieve their goals. Systems trump willpower almost every time, so having this as your default makes it happen without you thinking.

3. Have a six month emergency fund

A high priority before investing regularly should be six month’s of monthly expenses tucked away as savings in a form you can liquidate easily in case of trouble or a serious emergency. Often, you won’t have to lean on this extreme and drain the account, but if COVID showed us anything it’s how wrong initial estimates of a shock can be. Preparing for stormy weather is good planning.

The sad truth about these financial resiliency posts is they came about from people I know being in financial trouble during COVID that should not have been. While job loss, cutbacks, credit over-extension, or curtailed payments were main catalysts, the underlying cause was that the people involved had no cushion in their finances. Almost everyone was living paycheque to paycheque. Few had fixed roofs while the sun was shining.

Cushions against short-term shocks are important (we’ll deal with what to do if you also have debt issues in the next item.). The key thing to take away from this item is start putting the money aside in a place you could, if you had to, get to it to use for emergencies. I’d recommend using your 20% initially to pay into this emergency fund and get yourself buffer as soon as possible. If you’re keen on building investment, no matter what, split 10% to emergency fund and 10% to investments until your contingency’s topped up.

The problem here is that anything in low risk, short term, highly liquid savings, tends to not grow meaningfully. It shrinks in relation to the inflation rate, but think of this emergency fund as a cash cushion. Once you’ve got it, and have other investments starting to grow, you’ve got a lot more options. This should be your first major priority and milestone even if you have some debt load.

So, now you’re on your way to some stability. What do you do if you’ve somehow managed to let credit card debt get away from you? Or say a large student debt that’s an anchor round your waist. Let’s talk about that next.

4. Use Credit Wisely. Kill off debt.

If I had to pick one thing that normally trips up people in their financial goals it’s access to easy credit.

Few people recognize the insidious costs of consumer debt like credit cards until they get into trouble. On top of that, the funds you pay in interest suck away money that should be going to savings or investments. In fact, paying your short term consumer debt down to zero should be one of your highest priorities since it’s basically an additional, very high tax on your take home. And credit card companies want you to be in thrall to them and paying them a nice monthly stream (which is why when you’re debt free, you’ll notice them ratcheting up your credit limit to get you to buy bigger ticket items to hopefully carry a balance.).

So, what’s going on here? The concept behind credit is easy enough: you move future consumption you can’t afford now, into the present by paying a premium to do so, namely… interest. There’s no problem doing that if it’s necessary for reasons of liquidity (online companies, for example, only accept card payments) but the problem comes when you carry a balance. The interest rates are ruinous and credit card companies look at the interest first maintaining the principal balance for as long as possible. Worse, if you’re not paying down those pricinipal balances or even adding to them the card debt can put you into a death spiral of running to keep up with the interest and never getting the principal down.

Some easy rules of thumb: never use consumer credit if you don’t have to. Consider whether you really (really) need to buy the thing you want so badly. If you are solvent enough, move to a Visa or Mastercard debit card instead of a credit card (so you need the cash in your account to spend on items.). Before you buy something on credit, calculate the total cost of the thing including interest and make sure you still want to spend it. In fact, for any bigger purchase, say over a couple hundred dollars, have a cool-off period rule about a 3-day period before buying it to see if you rally need to buy it (I actually added things to a “To Buy” list and reviewed at the end of a week and it’s amazing how many things I’d never end up buying after that initial impulse was gone.). Don’t ignore the fact that much of what you read, see, or listen to on TV, social media, and outside is designed in subtle and not-so-subtle ways to get you to buy things you probably don’t really need.

For items that need to paid off via monthly credit card like subscription fees or the like, make sure they are manageable and that you’re paying off your balance every month. No balance. No interest payments.

Alright, this is all well and good but what do you do if you’re already carrying a balance and having trouble getting out from under it? This is where you need to make some concessions to your savings goal. Growing your savings or investments by 12% while you’re bleeding out to short term consumer credit at 20%-24% is not a game you can win longer term. Time for some hard decisions.

Is your debt something you can pay off in a year at 20% of your current income levels? If the answer to that is no, you should seriously consider putting together the type of plan I’ve suggested above and speaking to the bank about a consolidation loan where you ask to switch to a debit card and to give you a lower interest consolidation loan for the entire amount and pay it off monthly with them. You’ll save significantly and get on the road to resiliency faster.

Another (more risky) option is to switch to another credit card that transfers balances for up to 6 months at zero interest (or longer if you can negotiate it.). This is becoming an increasingly common switching strategy for some card companies and if you can be disciplined about only using the card for essentials and paying down as much as possible, you can dig yourself out of significant holes to get to a more financially healthy you. Try to make sure you are not tied to remaining with the card for any length of time after switching since you could always switch again (to another company’s card) if need be, particularly if your credit looks much better after the first switch.

Ultimately though, you are going to have to pay down some debt, so what you need to do here, is start splitting your 20%. 10% goes towards the emergency fund, the other 10% goes towards paying down principal on your short term consumer debt. Yes, I know it is painful. And feels counterproductive. But it’s the strong medicine part of the lessons.

Why not put the full 20% against the debt principal? It’s a good question as most people would say kill off the debt first. In my experience, though, most people that do this end up paying down their debt only to find some later crisis causes them to then have to take on more debt. They pay it down just to fill it up again. While splitting between principal repayment and emergency fund seems counter-intuitive and takes longer, I think it has three advantages even if it’s more expensive and slower in the long run than the straight debt route.

- Your debt does not expand. If you get into real trouble and you’ve only been paying off debt, you don’t need to take on more debt to deal with the emergency. You can lean on your emergency fund a bit.

- Psychological: Having cushion while paying down your debt makes you feel like you’re getting somewhere . If all you’re ever doing is paying down debt you are going to sooner or later get despondent about things, break discipline, and likely get yourself back into trouble. This way, even if it’s not the most mathematically efficient or cheapest, ends up at least feeling like you’re making progress (doulbe progress, actually), and keeping a positive mindset during the hard build part of the process is important.

- You’re going to be better off overall than you were before. As you pay down, debt servicing will be cheaper and you’re going to have cushion banked

Fin

So, yes, the rules are simple. They may seem too simple. That’s kinda the point. If you can stick to them, you’re going to be well on the road to financial resiliency and independence and a while suite of financial goals you may have.

Don’t be deceived, though. While simple, getting started takes some effort initially and for the first little while to get these rules into a system of habits. Once you get past that initial hump though, these rules will help you get to the point of greater financial resiliency.

Now that you’re cleaning up your resiliency and have your emergency fund sorted, how do you even get started growing your assets once you setting 20% of your income aside? That’ll be our next post on this topic.

Let me know what you think about the post on Mastodon @awws or via email hola@wakatara.com . I’d love to chear feedback about what similar or other processes or approaches may have worked for you or tweaks to the above. What have been your best finance systems to gain resiliency and stability? Even better, (reasoned) opinions on why I might be wrong and what might be even better or stronger changes that may have worked for you.